Home: Blog: 2006-02-04 On Philosophy

Home: Blog: 2006-02-04 On Philosophy Home: Blog: 2006-02-04 On Philosophy

Home: Blog: 2006-02-04 On Philosophy Mesolithic abstraction (5000BC)

Mesolithic abstraction (5000BC)

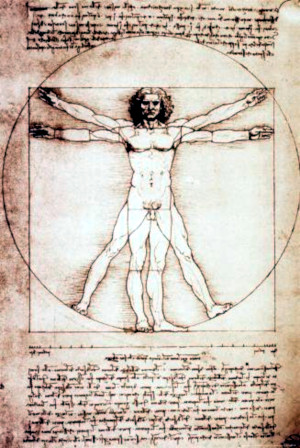

Eyes/nose/mouth/arms all instantly recognisable,

though no human actually looks like thisOur understanding of the world has developed as our species and our societies have developed. Living among species stronger and faster than themselves, early humans relied on intelligence to survive. They cooperated to protect themselves and their children, and to find food. Instinctive behaviours increasingly gave way to conscious planning, an evolutionary change which allowed our strategies to adapt ever more quickly to experience, as we can decide to try something new far more quickly than evolution will favour a tendency to do so.

Retaining a mass of unrelated facts is neither easy nor much profitable. Natural selection continued to favour humans whose brains formed patterns with the information they took in, building generalisations, which could in turn be extended to make predictions, and plan effective action. We create generalisations by abstracting: blending facts, and removing what they do not have in common to leave a consistent, and hopefully predictive, rule. If apples fall, and rocks fall, perhaps everything falls: including a boar chased into a pit by hunters. So helpful was this trick of abstraction that humans less fluent in it lost out to their brighter siblings in the competition to survive and breed, and humanity became ever more skilled in abstract thought.

One of 20bn neurons in your cerebral cortex

One of 20bn neurons in your cerebral cortex

This computer is a clumsy toy by comparisonAs we accumulated abstractions, we began noticing features that the abstractions themselves had in common, developing the 'meta' abstraction we call reason. Reason allowed us to combine known abstractions to discover new ones. The exponential increase in knowledge this created was such a powerful survival advantage that not only the ability to reason, but the drive to do so, was burned by evolution into the very pathways of our brains.

Aztec Rain God Tlaloc

Aztec Rain God Tlaloc

Front Gate of the National Museum

of Anthropology in Mexico CityThis compulsion to think soon led us to ask questions we could barely understood, let alone answer. The water we needed to irrigate our crops came from the rain, but where did the rain come from? For want of information, we formed answers by analogy. We give water to our children, so the sky is a father giving a water to us.

I don't suggest this reasoning to deride it. When first suggested, and given the information then available, it was probably the best answer available. It relies on on inductive reasoning, which predicts that the unknown will resemble the known: a method which often works, or we would never have become inclined to use it. (Now that we have more information, though, the sky father thesis is harder to defend.)

In any event, in our early human society, there came a dry spell, and we desperately needed rain. We applied our 'knowledge': the sky is a father which gives us rain. If he isn't giving us rain, therefore, he must be withholding it. And as we sometimes withhold things from our children as a punishment, perhaps we in turn are being punished. But what would the sky father want from us? Well, by analogy again, what do we value? Grain, meat, even our own lives: perhaps burning an offering, so that the smoke reaches the sky, will appease His anger.

Of course, once the sky father had a personality, it was only a matter of time before someone claimed to have spoken with him, and offered to act as intermediary. Perhaps they even believed it: but they certainly believed that the meat offerings which the sky father tended to leave uneaten should not go to waste. Freed from the need to feed themselves, these priests became the first philosophers: humans whose role in society was to understand the world. Their teachings become the first philosophy.

And still, humanity's understanding of the world developed as our species and our societies developed. The animistic spirits inhabiting nature which bullied and terrified early humanity developed first into the divinely privileged race of anthropomorphic gods living it up rather wantonly above slave society, and then the single, absolute, capricious, personal God, who stood behind the power of the divinely appointed King, who in turn stood behind the feudal Lords.

And still, humanity's understanding of the world developed as our species and our societies developed. The animistic spirits inhabiting nature which bullied and terrified early humanity developed first into the divinely privileged race of anthropomorphic gods living it up rather wantonly above slave society, and then the single, absolute, capricious, personal God, who stood behind the power of the divinely appointed King, who in turn stood behind the feudal Lords.

As capitalism and urbanisation undermined the power of the aristocracy, their god too had to be tamed. The rationalists wrested knowledge back from Him, and returned it to human minds. They politely said that reason was divine, but that just meant that even God was not exempt from its rules, and should stop interfering. Theism drifted towards Deism.

Social change was now driven not by what we thought, but by what we were discovering, and philosophy had to turn its attention from the inside of the human skull to the view through the eyes. Increasingly, new intellectuals weren't priests or philosophers but scientists, and among the philosophers the empiricists overtook the rationalists. We could not learn about the world just by thinking, we had to look, to listen, to experiment. Our senses, not our thoughts, were the source of knowledge.

Alfred J. Ayer

Alfred J. Ayer

Author of "Language, Truth and Logic"But if all that we knew of the world was what we could see of it, did it even continue to exist when we weren't looking? In the words of the famous question, if a tree falls in the forest when there is noone there, does it make a sound? The empiricists struggled with the problem. George Berkeley announced that it did, because God heard it even when we didn't. Indeed, to him, to exist meant to be an idea in the mind of God. David Hume gloomily but honestly pointed out that Berkeley was a wild optimist without a shred of proof that God was paying attention at all (or was even there...), and that there was very little we could really know at all. Don't get depressed thinking about it, he finally advised. Play backgammon instead. In modern times, Freddy Ayer and his Logical Positivists denied the question even had a meaning. Empiricism, which had begun by looking outwards at the world, was retreating deeper and deeper into the mind, leaving psychology the only true science.

Empiricism started from the assumption that we knew nothing except that we experienced sensation, and sought to create all knowledge from there. It was a heroic project in its way, but that first assumption was simply not true. We don't begin philosophising at birth, without knowledge, without a history of existence. In reality, we grow in the world, learning all the time, and philosophise precisely to understand better what we already know. It was inevitable then that having disconnected humans and human thought from reality, empiricism collapsed first into the honest nihilism of Hume, and finally into the meaninglessness of modern subjectivism, which democratically asserts that all ideas are equal, and that truth and falsity are outdated concepts - though on what basis we are to accept this idea if not as truth is not entirely clear.

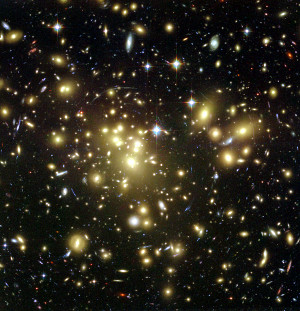

Hubble's view of galaxy cluster Abell1689

Hubble's view of galaxy cluster Abell1689

It was there before Hubble saw itIn the end, it was materialism which dared to say that the world existed even when unobserved, and that we can know this not through an argument proving it, or even a particular experiment, but through the persistent experience of a lifetime, the shared experience of humanity, and the very fact that we exist as we are.

In other words, materialism asserted the truth of that which the very evolution of our species depended on and therefore implied: a material world which existed independently of our thoughts about it, in which cause led to effect, and truth described the present and predicted the future, thereby making the human tendency to distinguish it from falsity an evolutionary advantage, and not a random neurosis.

Bosch's view of hell So far, this history has discussed metaphysics, which attempts to answer the question "what is?" Humanity was concurrently struggling with ethics, or "what is good?"

Bosch's view of hell So far, this history has discussed metaphysics, which attempts to answer the question "what is?" Humanity was concurrently struggling with ethics, or "what is good?"

The priests, the first philosophers described above, said that good was what a god said it was. But this begged the question. Did God choose moral laws arbitrarily, or because they were good laws?

If the former, then what goodness is there in submitting to random dictats, even if spoken by a god? It might be wise to obey, given the prospect of divine reward, or the alternative of hellish punishment, but where is the ethical value in doing what the bully wants? It would seem nobler, somehow, to defy him.

However, if God chose his rules because they are, in fact, better than other rules, then their goodness lies not in their divine ordination, but in some other standard of good and evil which exists independently of Him. Adding God to the problem explains nothing.

In a backlash against theism, others hold that ethics are merely personal preferences, or social prejudices, without any objective basis. This ethical subjectivism is a natural companion to philosophical subjectivism described above. However, of all the people who I have heard nominally adopt this position, I believe I have only met one who really understood what it implies. Most seem to believe that it simply indicates a kind of liberal tolerance, such as a refusal to condemn homosexuality or the use of drugs, or a kind of cultural open-mindedness which does not arrogantly assert the superiority of one tradition over another.

But ethical subjectivism avoids unjust moral condemnation by destroying the basis all moral condemnation. Offered as an alternative to bigotry, it leaves no grounds on which bigotry itself may be criticised. It ultimately implies that human revulsion at murder, rape, or torture is mere prejudice. True ethical subjectivism would be akin to psychopathy.

You certainly don't need to be an ethical subjectivist to reject homophobia: and if you are, you have no grounds on which to condemn it.

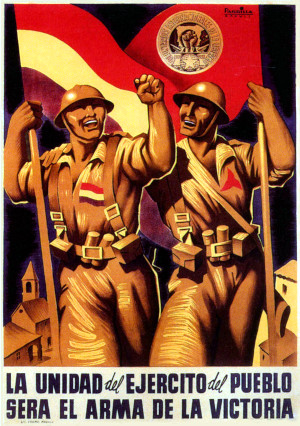

The International Brigade

The International Brigade

Risked their lives to fight fascism in another countryThe idea that morals must be either God-given or arbitrary has been pushed hard by theists. They hope that this logic, combined with our natural sense that what is good is no mere preference or convention, will force us to accept a god. And some atheists have fallen into the trap of accepting their premise, and arguing some form of moral subjectivism or cultural relativism. But it is a false dichotomy. If God defines morality, morality is arbitrary anyway: the preferences of whomever happens to be most powerful are no less subjective than those of anyone else. But more importantly, the mystery of a godless but still objective basis of morality is no mystery at all. We all know it, and apply it daily.

First, the question of what is good or bad must be separated from the question of what makes us feel things are good or bad. Like any other feeling, this was programmed into our brains by evolution. An inclination to co-operate with and protect those who shared our genes promoted the survival of those genes. This is why altruistic love is most passionately felt for our children, then our immediate family, then our tribe (in early human society, essentially an extended family), and most weakly for humanity as a whole.

Similarly, our tendency to fear and be suspicious of aliens - of rival tribes foraging our forest - was, too, favoured by natural selection. Motivation to fight to defend access to scarce resources was clearly once an aid to survival (even if it now threatens to kill us all). And so, in a complicated algorithm, evolution balanced altruism towards others proportional to how closely they were related, with competition against them inversely proportional to it.

And evolution favoured not only our own tendency to follow this mix of altruism and patriotism, but to reward those around us who did so. As a result, this winning strategy was enforced by each human's own conscience, and by the approval (or disapproval) of others.

But evolution only explains our feelings about human behaviour. It doesn't address the question of whether the words "good" and "bad" have any meaning outside those feelings. And as human beings developed the compulsion to reason, we asked ourselves this question endlessly.

And we answered it, again and again.

To do good is to do as you would be done by. This "golden rule" has been expressed in a thousand ways in a thousand texts, religious and non-religious. It is found in Buddhism, Christianity, Confucism, Islam, Judaism, Taoism, and Zoroastrianism. It is equally found in Humanism. It is in the Code of Hammurabi, underlies the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and is understood by every parent who has ever asked a child "would you like it if someone did that to you?"

Ethics are a universal standard. The moment we claim a right to be free from harm inflicted by others - not to be beaten or raped, cheated or lied to, enslaved or killed - we necessarily extend it to others. Not because any god says so, but because not to would be self-contradictory. It is true as two plus two is four is true: whether God says it is, says it isn't, or doesn't exist at all.

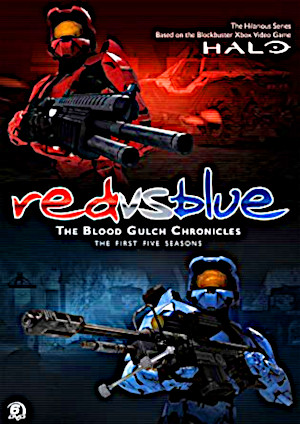

Red vs. Blue: a modern Beckettian satire on tribalism,

Red vs. Blue: a modern Beckettian satire on tribalism,

as enacted by characters from an Xbox game. Really.So ethics have an objective, rational basis in simple reciprocity, and this is usually backed by the feelings of empathy and altruistic love which evolved because they helped tribes survive. But what of the other feeling evolution left in us: the fear of, and urge to compete with, those outside our tribe?

The conflict between these impulses mattered little before we acquired the power of reason. In any given situation, the greater impulse prevailed. But as thinking animals, it torments us.

The contradiction is revealed most sharply by war. Bombs kill innocents. Adults and children die huddled in their homes in terror and despair. Each side feels outrage when this happens to its own people, and yet continues to visit it on its enemy. In the most horrible transgression of the golden rule, tribal competition drives us to do to others precisely what we think inhuman when done to us.

This irrational evolutionary hangover creates painful cognitive dissonance. We become desperate to justify the plainly unjustifiable. Lists of atrocities committed by them against us are passionately compiled. Any criticism of our behaviour is met with accounts of theirs. Racial and cultural differences are offered to prove that they are dishonest, parasitic, and evil: essentially, that they are inhuman, and therefore outside the protection of human ethics. And history is invoked to burden people now living with a guilt - somehow supernaturally inherited - for things done by people long dead.

Dressed up as a principle, this anti-principle is given names like loyality, patriotism, and nationalism.

Rationally, it is nonsense. It is too incoherent even to rise to the level of an idea, even a mistaken idea. It is an subrational noise covering an indefensible but powerful human impulse, an attempt to drown out our knowledge that "do as you would be done by", though we only feel motivated by when extending it to people we feel kinship with, cannot justifiably be withheld from anyone.

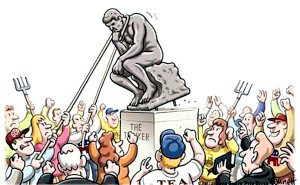

At a subliminal level, even the nationalists themselves are troubled by this. This is why nationaism so often goes hand-in-hand with anti-intellectualism, and a contempt for a snobbish "elite" who demand ethics for all: the bleeding hearts, the foreign apologists, the traitors. As the expression of an evolved impulse, nationalism is a matter of the "gut". It feels right, and our whole bodies reward us with a sense of collective strength and existential justfication when we indulge it.

At a subliminal level, even the nationalists themselves are troubled by this. This is why nationaism so often goes hand-in-hand with anti-intellectualism, and a contempt for a snobbish "elite" who demand ethics for all: the bleeding hearts, the foreign apologists, the traitors. As the expression of an evolved impulse, nationalism is a matter of the "gut". It feels right, and our whole bodies reward us with a sense of collective strength and existential justfication when we indulge it.

Looking for an ideology which will most easily win you passionate support and power? Try nationalism.

This is why populism is popular. Our very bodies respond to a sense of group identification in the same way they respond to heroin. This appetite is the most poisonous fruit of our evolution.

Nor is it unique to the political right. There are nationalists who claim to be socialists, and the left has extended tribalism as a ideology, and as a method, beyond nations. Truly progressive movements, opposing (for instance) the unequal treatment of women, or of black or gay people, have all developed factions which have crossed a line from organising all humanity against an injustice, to hating and dehumanising them under the cover of defending us. Their aim has degenerated from eliminating prejudices denying the individuality and freedom of each human being, to merely reversing them. They use language about others which would instantly be recognised as bigoted if used about themselves, justified by the same formulae of dehumanisation and collective and inherited guilt as the nationalists. They have discovered the joy and power, latent in every human brain, of tribalism.

Our evolved impulse to find a group to identify with, and feel a sense of security and power within it, is intoxicating: and it leads good people to do bad things. The first step in correcting it is to understand why we feel it. Then we must counter it, within ourselves and our movements.

This is not simple. Justice frequently involves taking sides. Badly treated workers and entitled to strike, and to denounce their employers. Citizens denied liberty have not only the right but the responsibility to fight and overthrow dictators. A social minority facing discrimination should of course fight to end it. But in all these cases, the sides should be defined by what they do, by the decisions they make. It is a complicated, intellectually discriminating position: and all the time, our tribalist impulses will be encouraging us to manufacture rationalisations for what are, in truth, prejudices. But the moment we form a judgement about a human being based on anything other than their personal, voluntary choices, we become throwbacks to the first violently squabbling tribes who killed others for taking apples from their trees.

Ultimately all politics are an expression of ethics, though many politicians, particularly socialists and anarchists, are extremely shy of the subject. A macho jargon of scientific analysis, social progressiveness, and historical inevitability is used to avoid acknowledging the somehow slightly embarrassing fact that the aim is to do good. It is understandable. Oppressors and exploiters of every stamp, and above all religion, have given "good" a bad name, and associated it with being patronising at best, and downright oppressive at worst.

Ultimately all politics are an expression of ethics, though many politicians, particularly socialists and anarchists, are extremely shy of the subject. A macho jargon of scientific analysis, social progressiveness, and historical inevitability is used to avoid acknowledging the somehow slightly embarrassing fact that the aim is to do good. It is understandable. Oppressors and exploiters of every stamp, and above all religion, have given "good" a bad name, and associated it with being patronising at best, and downright oppressive at worst.

The left usually, therefore, speaks of solidarity, rather than ethics, morality, or love.

But there is a danger here. The problem with the word solidarity is that it is not inherently univeral. Solidarity can be restricted to people of a particular country, sex, race, or religion: making it the very opposite of ethics. True solidarity - the resolve to defend for others the rights we demand ourselves - rises to a principle only when extended to all.